How an I.O. Shen knife is like a Samurai sword

Japan has a well deserved reputation – dating back over 1,000 years – of producing some of the best and sharpest blades, none more feared than the Katana, the traditional sword of the Samurai warrior.

Japan has a well deserved reputation – dating back over 1,000 years – of producing some of the best and sharpest blades, none more feared than the Katana, the traditional sword of the Samurai warrior.

Although you don’t come across too many Samurai warriors in modern day Japan, the Samurai sword is still made in Japan using the same ancient methods and rituals in place since around 900 AD. The Katana has a reputation for being one of the sharpest, if not the sharpest, sword in the world, and anyone who has seen The Bodyguard with Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston will remember the scene where the silk scarf is cut in two just by falling on the upturned blade.

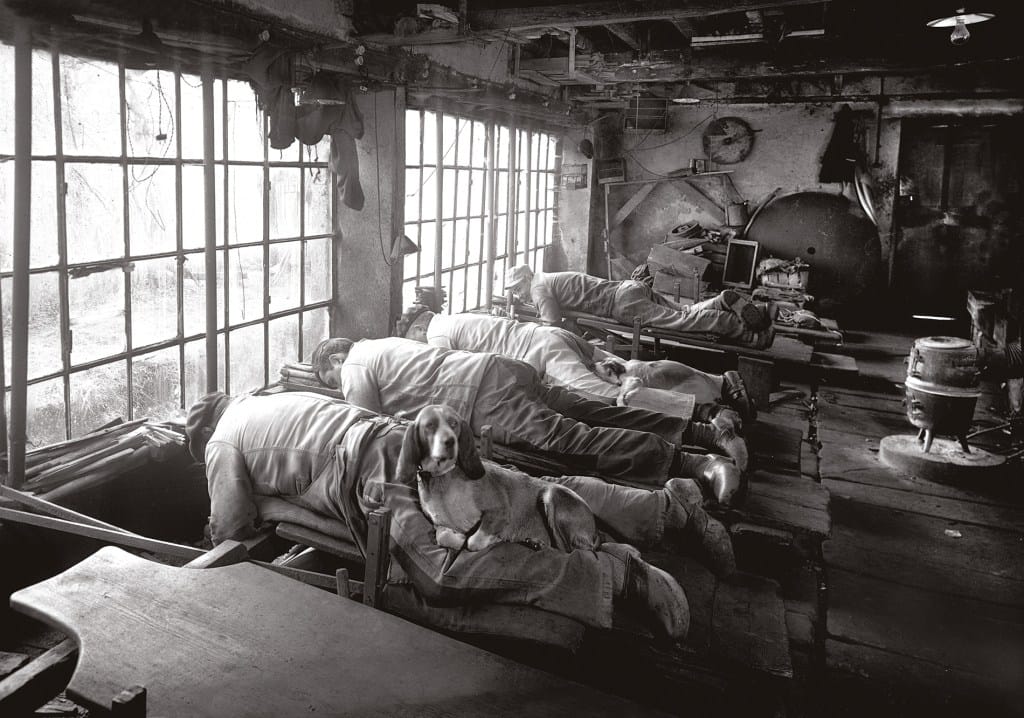

The Katana is made using the same techniques that have been used for centuries, taking iron ore from river sand and combining it with charcoal in a traditional ‘tatara’ furnace. Although the craftsmen making the swords wouldn’t have known the chemistry behind their technique, it is the blending of the iron with the carbon which makes the resultant steel much harder than the iron from which it is derived.

The Samurai sword was designed not to pierce, like the European style epée sword, but to slash, where the warrior used his whole body force in battle, chopping head and limbs off his foes. A somewhat grisly indicator of the ‘power’ of a Katana which was used in more brutal times was a number indicating how many bodies the sword could slice through – a ‘five body’ blade being the maximum on record in Japanese museums. Samurai used to have free rein to test their swords on condemned prisoners, but today it’s more usual to use bamboo posts.

Japanese swordsmiths used a number of techniques to make Katana swords as hard and sharp as they are – the smelting technique described above produced high quality steel which was then divided into two types – slightly harder, and more brittle steel that formed the cutting blade, and slightly softer steel that was used to form a sheath around the harder steel blade tip. This clever design means that the whole blade is less brittle than if it were made entirely of the harder steel. The final part of the process is where the blade is forged by heating it to 1500°C and worked so that the steel is able to maintain its sharp edge. This stage – called ‘quenching’ – is a critical part of the process and requires great skill: one in three blades are lost at this stage due to cracking.

Although these techniques resulted in Samurai swords being some of the hardest and sharpest swords in the world, in fact the power of the sword in battle relied less on its sharpness and more on the brute force of the Samurai warrior wielding it. In practice these swords were not that sharp compared with modern kitchen knives for example, and seen in cross section, the cutting edge is actually quite a broad 120°, much broader than a standard kitchen knife. This also makes Samurai swords quite hard to make very sharp, as the process requires a large amount of the steel in the blade to be removed.

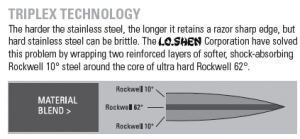

Since keeping a set of Samurai swords in the kitchen is a little impractical, you may be interested to know that the next best thing is a set of I.O. Shen knives. Just like the process used to make a Samurai sword, I.O. Shen knives use a hard inner metal surrounded by an outer softer metal ‘sheath’, and for pretty much the same reasons as the ancient (and modern) Japanese swordsmiths.

Main image credit: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shinken-sword.jpg