Knife sharpening has been around as long as knives have been around and – depending on your definition of what a knife is – knives and things to sharpen them have been around for more than 3 million years, or at least these are the oldest artefacts discovered by archaeologists that show evidence of having been used as cutting tools and ‘sharpeners’.

These were discovered in Kenya and dated to 3.3 million years ago and in fact they pre-date modern humans. The first human made tools to be discovered were made by ‘Homo habilis’ (which means ‘handy man’!) 2.6 million years ago.

Most people are familiar with the Stone Age ‘handaxe’ – a piece of flintstone sharpened by flaking off shards of the flint using pieces of a harder rock to expose a sharp ‘blade’. The earliest handaxes date back to 1.6 million years ago and have been found right around the world, from southern Africa to northern Europe and India.

As humans progressed through the bronze age and the iron age, the sharpener of choice – as it still is for many knife owners today – is stone, or more precisely one used specifically for sharpening – a whetstone, historically made from either sandstone or emery stone (although modern ones are made of different materials).

The Egyptians used sedimentary rocks like sandstone and limestone to keep their copper and bronze blades sharp and the ancient Greeks were apparently impressed by ‘Cretan stone’ for sharpening and used olive oil to keep their stones cool while honing their blades. The Romans took things a stage further, even using ceramic sharpening rods alongside the more traditional emery stone.

The next group of sword and blade experts in history were the Vikings, who took things to another level again. They were really the first to ‘mass produce’ knife sharpening stones and were one of the first examples of a ‘country’ (let’s call it Norway) exporting one of its products to other parts of the world.

Archaeologists have found large quantities of worked stones in present day Norway which can only have been used for sharpening. So perhaps we should forget about any thoughts of trade being all about precious items and think about the Vikings turning up on the shores of England with the latest knife sharpening technology – pieces of (very hard) stone. Maybe the Viking (partial) invasion of Britain was the result of a trade dispute?

By the Middle Ages – in Britain at least – someone had invented the rotating grindstone, which was able to sharpen a blade much more quickly than the traditional whetstone. Because it was quite a large piece of equipment it tended to be used to make knives rather than just keep them sharp, so most people still used whetstones for this. Around this time there’s also evidence of pieces of leather being used as ‘strops’ to keep knives sharp.

The Middle Ages were also when people involved in the various stages of making knives and swords got different names – ‘bladesmiths’ made the blades themselves, scabbards were made by ‘sheathers’ and ‘gilders’, and ‘furnishers’ and ‘grinders’ were also part of the manufacturing process.

But it was the ‘cutlers’ who ultimately designed the knives and swords. A ‘cutler’s guild’ was set up in Cheapside in London in the 13th century and by the 16th century this guild had incorporated all of these different trades under one roof.

Things continued pretty much as they were until the next disruption – the Industrial Revolution – which brought mechanisation to the production of knives and sharpening methods, starting with watermill-powered grindstones and graduating to steam power, drastically cutting the time involved in making knives and making the sharpening of the blades quicker and more accurate.

And the rest, as they say is history!

For a few articles we’ve already posted about some of the more recent history of knife sharpening check out our article on ‘Moletas‘ and our article on Ballarat butcher Peter Loughnan on what working as a butcher was like before the arrival of electric knife sharpeners.

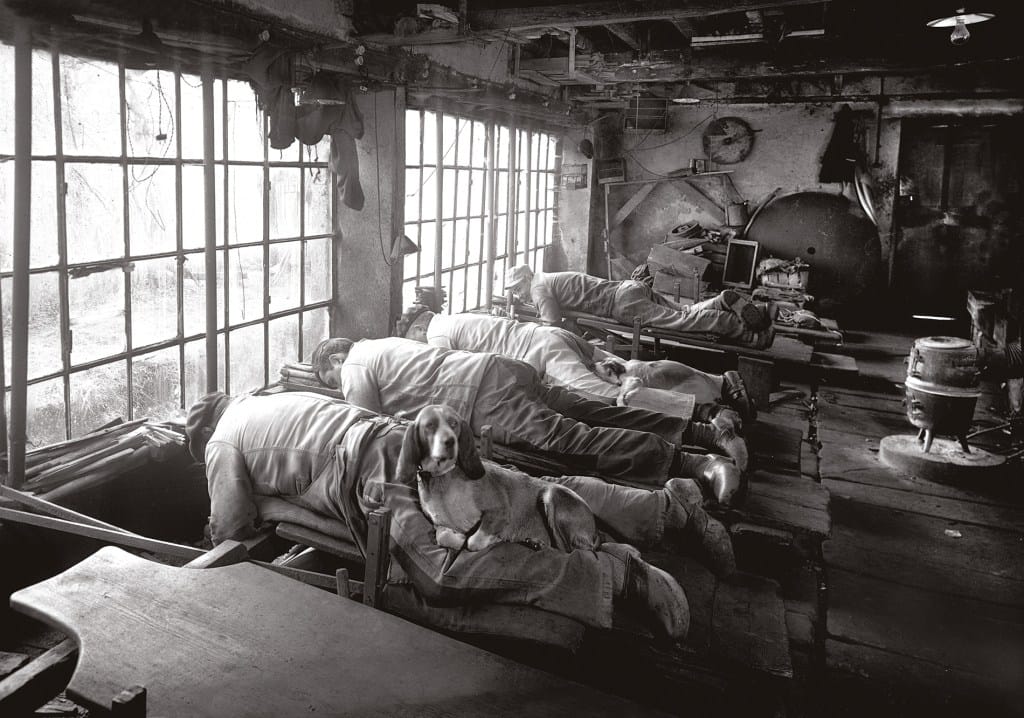

Main photo credit: Everin Seclaman

Photo shows French knife grinders who worked on their stomachs in order to save their backs from being hunched all day. They were also encouraged to bring their dogs to work to keep them company and also act as mini heaters by having them rest on their owners’ legs. They were also called ventres jaunes (“yellow bellies” in English) because of the yellow dust that was generated by the grinding wheel.